This is intended as a general discussion about tax. I'm an accountant by profession, but I'm British, so I encourage my overseas counterparts to participate as I'm not an expert on e.g. US tax.

That said, I'm also an economist, and I want to kick things off by addressing the popular idea that increasing tax rates will increase government tax revenues.

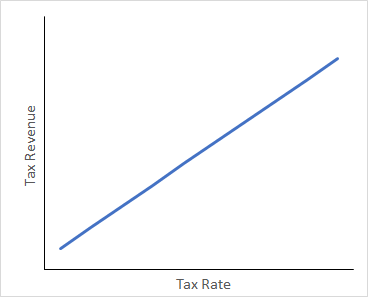

A lot of people think that the relationship between tax rates and tax revenue is a straight line:

That is, tax revenue increases hand in hand with the tax rate. From a low resolution point of view, that makes a lot of sense, but this is far too simple and is an unrealistic representation of the real world.

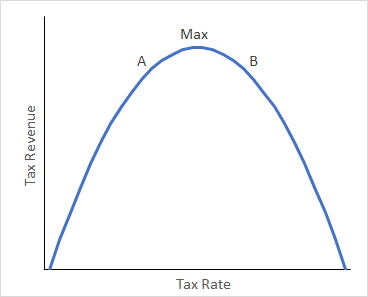

In reality, the relationship looks much more like this:

This is the Laffer Curve, named after Art Laffer (a former Reagan adviser, and truly vile person, but his contribution is widely accepted as a useful illustrative model)

Let me explain:

That said, I'm also an economist, and I want to kick things off by addressing the popular idea that increasing tax rates will increase government tax revenues.

A lot of people think that the relationship between tax rates and tax revenue is a straight line:

That is, tax revenue increases hand in hand with the tax rate. From a low resolution point of view, that makes a lot of sense, but this is far too simple and is an unrealistic representation of the real world.

In reality, the relationship looks much more like this:

This is the Laffer Curve, named after Art Laffer (a former Reagan adviser, and truly vile person, but his contribution is widely accepted as a useful illustrative model)

Let me explain:

- The initial gradient is steep because (in a progressive tax system) more people are caught in the lowest tax bracket than each subsequent higher bracket

- To the left of the maximum, increasing marginal tax will increase tax revenue, albeit with diminishing returns, and that makes sense because there are fewer and fewer earners in higher income brackets

- To the right of the maximum, increasing marginal tax actually reduces tax revenue for a number of reasons:

- The rich begin to emigrate to countries with lower tax. In pure currency terms, the rich contribute the majority of tax revenues. In percentage terms, they arguably contribute less than a lot of ordinary people (especially if you consider consumption tax)

- Higher marginal tax is an incentive for tax avoidance and evasion

- Higher marginal tax is a disincentive to work/produce more at the margin

- If marginal tax were 100%, then marginal tax revenue would be zero, because nobody would bother doing anything that would incur tax. Now extend that logic backwards and you end up with a bell curve

- So where are developed economies on this chart? Nobody knows for sure, it is impossible to empirically prove in real time, and it changes every year

- Politicians on the left will argue for higher taxes i.e. that the economy is at point A

- Politicians on the right will argue for lower taxes i.e. that the economy is at point B

- The only correct answer is that significant changes in either direction will probably reduce tax revenue, because Western economies are unlikely to be very far from the maximum point; it is no accident that tax bands are broadly comparable between developed countries

Last edited: